Gone Squatchin'

When I was a kid, I typed so slowly that it freaked people out. Teachers sent letters home. Watching me painstakingly hunt and peck for each key was so excruciating for my mother that one day I walked into my room and found a copy of Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing on the bed, presumably left there in hopes that I would mistake it for a video game and accidentally develop a marketable skill. I never so much as opened the box, purely out of spite. I knew I was a slow typer. I didn’t care. Typing would not enhance my ability to play Perfect Dark on my Nintendo 64, therefore it was of no use to me.

One afternoon in sixth grade, an agonizingly slow Google search led me to a vBulletin message board full of fellow Perfect Dark enthusiasts. A few clicks later I stumbled into a corner of the site where a few dozen people were writing and posting stories set in the game’s cyberpunk sci-fi universe of flying cars and alien conspiracies circa the distant future of 2023. For as long as I could remember I’d been making up elaborate stories to entertain myself during long car rides or when a teacher was talking about math, science, or typing. Behind the curved glass of my Dell’s monitor was a place where other people were doing the same thing.

In the space of about six weeks I could type faster than my parents. Now my daydreaming had focus. I wasn’t just tuning out pre-algebra because I was bored – I was doing it because I needed to figure out what was going to happen in the next chapter of the story I was posting that night. I scrupulously avoided running in PE, but I’d sprint from the school bus to my keyboard so I could hammer out the continued adventures of the secret agents from Perfect Dark trapped on the dinosaur-infested island from Jurassic Park. The story’s title, Jurassic Dark, remains the best piece of advertising I’ve ever come up with. At least half a dozen people on the message board enthusiastically consumed each installment and cheered me on to write more. Soon I was spending far more time writing about Perfect Dark than actually playing it.

Sometimes after posting a new chapter I’d just sit there refreshing the forum page again and again, waiting for the view counter to tick up, thinking This is the only thing I want to do for the rest of my life.

In 2015 I wrote a script about a lonely teenager in the early 1980s who befriends an eccentric guest at his aunt’s hotel, only to discover that his new friend is a time traveler from the distant future of 2015. The script did well in a hoity-toity screenplay competition, which attracted the attention of a literary manager who offered to represent me and help get my work sold and produced. Before long she set up a meeting for me with a producer who’d read my script and wanted to make it into a movie.

In the leadup to the meeting I retreated into the same fantasies of Hollywood stardom that I’d entertained since the Jurassic Dark days: Being interviewed about my creative process by Terry Gross. Making an incendiary, politically charged acceptance speech on a nationally televised award show. Getting emails from my idols, Paul Thomas Anderson and the Coen Brothers, telling me they were huge fans of my work and would I like to hang out sometime?

In the producer’s office I sipped from a bottle of water and bobbed my head as he told me how fabulous my script was, and how with just a few minor tweaks it would be something he’d love to bring to the screen. For one thing, it needed a romantic subplot. More scenes of the kid and the time traveler palling around having a good time. And it needed to be ten pages shorter.

A month later, fresh from rewriting a third of my script, I sipped from a bottle of water and bobbed my head as he praised all my changes and served up a new batch of recommendations. We should really dig into the bad guy’s backstory so we get what he’s all about. The kid and the time traveler should go on a road trip at some point. And it was still running on the long side, so I should cut another five pages.

A month later, fresh from rewriting two thirds of my script, I sipped my bottled water as he assured me we were very close, and there were just a few more things I needed to add to the story – while simultaneously making it shorter. A couple bottles of water after that, my script had mutated into a lumpen, unwieldy mishmash of subplots and montages to accommodate the ever-changing whims of a wealthy middle-aged businessman.

As I left what wound up being our last meeting with a fresh set of notes, I asked him, “Is there anything in the script I should make sure not to change for the next draft? Anything you really like?”

He gave me a blank look and shrugged. “Nah, not really.”

Our next meeting got rescheduled a couple times and then never happened.

Afterwards I wanted to dig through the mountain of discarded drafts to find the last one that was truly mine, before the producer had laid his eggs in it, and have my manager send it around again. But by the time I did, Stranger Things had come out, and my manager explained that the development market was now so oversaturated with science fiction stories about kids in the 1980s that producers weren’t interested in that anymore, so my script never got made into a movie.

A couple years later I wrote a TV pilot about a woman who discovers that the residents of her small town are getting their brains scrambled by an alien signal from deep space that plays on their radios after dark. Her attempts to stop this clandestine invasion are complicated by the fact that it’s 1964, she’s white, and is secretly having an affair with a black woman. As the story unfolds, the prejudices of the other humans in her racist, segregated hometown wind up being almost as much of a threat as the aliens brainwashing the locals.

Accuracy was important to me, so while writing the script I went hog wild on research about the Civil Rights Movement, the physics of radio waves, sundown towns, astronomy, radio DJ lingo, and Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign. I retooled and reworked the script again and again, painstakingly organizing story beats so that the setup for the mystery and the protagonist’s secrets would unspool gradually over 60 pages. After more than a year of scribbling plot points in Moleskine notebooks and pushing the limits of how many Wikipedia tabs one browser window can support, I sent the finished product to my manager.

After a few minutes of small talk on the phone, she said, “My overarching note about your script is: why period?”

Why. I struggled to find an answer to such a weighty question, which had never come up in my many imaginary conversations with Terry Gross. Why did I, a straight white guy, feel I had any right to tell a story about a queer interracial relationship? Why had I poured so much effort into writing a story that, even under the most wildly optimistic circumstances, would be little more than a calling card to convince some producer I was a good enough writer to be given a job on Blue Bloods? Why was I even trying to pursue a career in the entertainment industry when it had thus far been nothing but dead ends and circlejerks?

“I don’t know,” I said. “I guess I just like making stuff up?”

“No, I mean, why is this script a period piece? Producers don’t want to read anything set in the past anymore, I’m hearing this from all over town. I feel like it’d be pretty easy to update this script to be set in the present day.”

I swallowed a few gallons of bile and attempted to politely explain why my story, in which Jim Crow segregation laws and a lesbian relationship were key plot points, wouldn’t be the same story if the action was transplanted to 2019. I explained that it went beyond plot mechanics – the setting was the story in so many ways. This was a story about contemporary issues like small town Americans getting brainwashed through the media and reactionary racial politics distracting us from real existential threats. Setting the story in the 1960s made it possible to explore those issues without turning subtext into text.

When I was done she said, “Uh huh” with the exact vocal tenor of someone who has been checking their email for the past several minutes. “Yeah, I just really think this would be a stronger sample if it were set in the present.”

Anyway, I never updated the script’s setting and she never showed it to any producers and it never got made into a show.

Around this same time my manager had secured me a job as a staff writer on a nonunion horror series about an evil tree that kills people. The working arrangement was what’s known in the industry as a “mini room” – a writer’s room where a small number of writers (in this case just myself and the head writer) work very hard to churn out as many scripts as possible as fast as possible so the studio only has to pay for a few weeks of work. As a writer this means you get burned out quickly and don’t make a living wage, but on the plus side you get the satisfaction of knowing these cost savings are creating value for shareholders in the hedge fund that owns the production company.

Despite that, and despite the fact that I don’t particularly like horror movies, I have a lot of fond memories of my early days as a cog in this finely tuned content machine. The production company rented a tiny room in a downtown coworking space for me and the head writer to work out of. Every morning I’d take the subway to the office, and before we started she’d make a selection from Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems for me to read aloud to set the tone for the day’s work. California sun streamed through the windows as we brainstormed various ways an evil tree could murder teenagers, most of which wound up being vine-oriented due to budget constraints: Vines bursting through chest, vines wrapping around throat, vines gouging out eyes… Each day she’d give me her pack of cigarettes and instruct me not to let her have one until she’d written a sufficiently gruesome kill.

This process produced over a dozen tense, complex, grimy, and thoroughly terrifying scripts that we were both proud of. After we finished each one, I’d save it as a PDF and send it off to the team of friendly and cheerful development executives at the streaming service that had bought the show. A few days later, they’d email the PDF back to us with their notes and an upbeat message about how we were rockstars who were totally killing it.

Collectively, the executives’ notes served as a sort of industrial strength powder sander, aggressively grinding away every misshapen odd and end that ran the risk of making the show unique. The graphic violence didn’t bother them, but they were very concerned by things like quiet, reflective moments of character development or instances of awkward and offbeat dark humor, which they deemed “confusing.”

In an early episode we’d written a scene where a group of high school bullies are beating someone up near a trash-strewn riverbed. One of the goons pauses the beating to grab a dirty baseball cap off the ground with a cartoon Bigfoot and the words “GONE SQUATCHIN’” emblazoned across the front. Laughing, he sets it atop the victim’s bloodied head, and then they resume the ass kicking. (Don’t worry - later in the series these bullies receive a vine-based comeuppance.)

Kind of confusing, do we need this? said the executives’ yellow text bubble next to the mention of the hat. We didn’t need it – the beating made just as much sense without GONE SQUATCHIN’ – so we cut it out, like we cut out a million other little moments of flavor and color and weirdness that signified that this show was the product of human imagination.

But we didn’t not need it. The episode wasn’t running too long. Hats with GONE SQUATCHIN’ printed on them are not expensive or difficult to find. The concept of a sociopath putting a funny hat on the person they’re torturing is not remotely confusing. And even if it was – even if someone who had sat through ten minutes of a show about an evil tree killing people was utterly flummoxed by the sight of a novelty trucker cap – would that really be the end of the world? Would that person’s response to not understanding two seconds of television be to stop watching the show and unsubscribe from the streaming service?

What if instead their reaction to being confused was to spend more time thinking about the show afterward? What if they attempted to assign some sort of personal meaning to the bewildering images they’d consumed? What if this process made them feel something? A generation of bright-eyed tech company middle managers are hard at work ensuring that we never have to learn the answers to these questions.

Anyway, the show got made and released and the streaming service didn’t promote it so nobody watched it and now the streaming service no longer exists so it’s impossible to see the show, and also the production company ratfucked me on pay at every opportunity.

After that, I spent four years working on a script about the life of a Renaissance painter called Caravaggio, who was one of the most revolutionary figures in art history and stabbed an unusually high number of people. I read a few books and spent three weeks in Italy visiting the places where Caravaggio used to hang out. In my script, Caravaggio is presented as a creative professional driven mad by an art industry dominated by wealthy, shortsighted patrons incapable of appreciating artwork that’s challenging or out of the ordinary.

“I just don’t understand who Caravaggio is as a character,” my manager said when I sent the script to her last spring. “I don’t get what he wants or what motivates him.”

She went on to offer a few vague recommendations for how the script should change, making the same sort of general statements about the plot that I used in college when called on to discuss a piece of assigned reading that I hadn't read. At some point I quit listening as it dawned on me that I was never going to be a professional screenwriter.

A script is basically a technical document for creating a bigger, better piece of art. A good script that never gets made is a lot like a good printer instruction manual: it’s impressive to other weird nerds who write printer manuals, but no normal person has any interest in engaging with it. I used to find that concept depressing.

But an unmade script is a script that isn't pruned of every moment that confuses a group of streaming service content managers. And functionally, how is an unmade script that different from a produced script which spends a few weeks buried on a "New Releases" tab before getting blinked out of existence so some rich guys can claim it as a tax write off?

Five or six weird nerds who write scripts have read my scripts and liked them. I'm proud of that. I’m trying to get my brain to squirt out the same chemicals it did when five or six people liked Jurassic Dark.

These days I write less and play video games more. I’m Flowers for Algernon-ing my way back into the chubby 12-year-old who couldn’t find the space bar. Cyberpunk 2077 is like Perfect Dark with more violence and swearing – essentially a big-budget adaptation of my fan fiction. Maybe 20 years from now there’ll be a video game about Caravaggio.

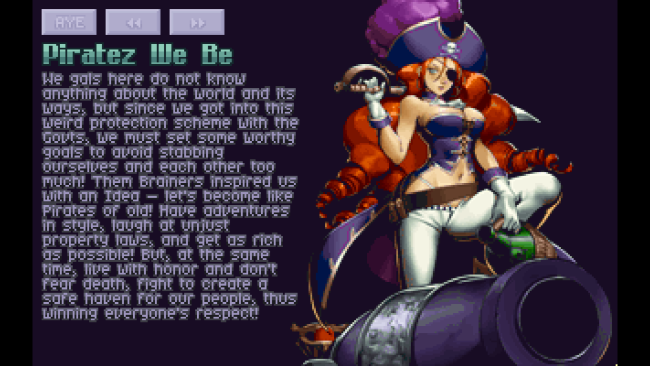

There’s a game I haven’t played that I think about a lot. It’s called X-Piratez, and it’s made by an indie game developer known only as Dioxine. He’s cobbled together bits and pieces from a bunch of 30-year-old DOS games like Doom, Wolfenstein 3D, and X-COM to make a strategy game where you command an all-female gang of fugitive mutant space pirates on an apocalyptic alien-colonized Earth. As you lead squads of chainsaw-wielding Amazonians in raids on alien factions with names like Sky Ninjas and The Star Gods, you uncover the dense, fully realized, and completely bonkers lore and backstory Dioxine has created for this virtual world – all of it conveyed in hundreds of thousands of words of text written in weird futuristic pirate jargon.

X-Piratez is available for free on Dioxine’s web site. Over the years multiple professional reviewers for major gaming websites have discovered it, played it, and rendered the same assessment: it’s an exciting, addictive, wildly original experience that also happens to be awkwardly, cringe-inducingly pornographic.

Every loading screen and menu is splashed with tacky, mismatched pinup-style anime nudity, much of it seemingly ripped straight from DeviantArt. None of it is in any way essential to the plot or gameplay. It’s just sort of there, for reasons nobody but Dioxine can understand. Kind of confusing, do we need this? Most strategy game enthusiasts, myself included, find this off-putting enough to avoid X-Piratez entirely. As a result, this thing Dioxine spent thousands of hours making has never picked up any mainstream attention or momentum outside of a small, committed fanbase who congregate on his message board.

A common theme on the message board is newcomers begging Dioxine to release a version of the game without all the sweaty, horned up visuals. Dioxine’s response is always the same: No. You don’t get it. Fuck you for asking. A direct quote from one of his smackdowns: “Please don’t ask me to insult players’ intelligence like that, because I won’t do it.”

When I daydream about success now, I don't think about Terry Gross or award shows or fangirling emails from Paul Thomas Anderson. I think about health insurance and a low-key day job that affords me the freedom to be like Dioxine.

I want to create bizarre shit with zero concern about whether anybody finds it confusing. I want to make no effort to promote it or profit from it or build a personal brand. I want to cultivate a miniscule audience of fellow weird nerds who stumbled on my work by accident and hesitate to recommend it to their friends and loved ones. I want to be smug and condescending to anyone who suggests that the stuff I make up should change in any way. I want to go squatchin’ and never come back.